What Is an Absolute Pressure Sensor and How Does It Work?

Date:2026-02-02

- 1 The Core Principle: How Absolute Pressure Sensors Operate

- 2 Key Specifications and Selecting a High-Accuracy Sensor

- 3 In-Depth Application Analysis: From Sky to Vein

- 4 Interface and Integration: The Digital Sensor Advantage

- 5 FAQ

- 5.1 Do absolute pressure sensors require calibration, and how often?

- 5.2 What factors are most important when choosing a sensor for altitude measurement?

- 5.3 How do medical-grade pressure sensors differ from industrial ones?

- 5.4 Should I choose a digital or analog output pressure sensor?

- 5.5 What does "long-term stability" mean in a sensor datasheet?

Pressure sensing is a fundamental capability that bridges the physical and digital worlds, enabling everything from weather forecasting to life-saving medical interventions. Among the various types, the absolute pressure sensor holds a unique and critical position. But what exactly sets it apart? Unlike sensors that measure relative to atmospheric pressure, an absolute pressure sensor measures pressure relative to a perfect vacuum, providing a fixed and unambiguous reference point. This distinction makes it indispensable in applications where knowledge of the true, non-relative pressure is paramount, from determining altitude to managing engine performance. Understanding its operating principle, key specifications, and ideal applications is crucial for engineers and designers across industries. At the heart of modern innovation hubs, specialized enterprises focus on advancing this technology. For instance, founded in 2011 within a leading national high-tech district renowned as a center for IoT innovation, one such company dedicates itself to the R&D, production, and sales of MEMS pressure sensors. By combining professional development with scientific production management, rigorous packaging, testing, and competitive pricing, they deliver the high-performance, cost-effective sensing solutions that power today's advanced applications in medical, automotive, and consumer electronics sectors.

The Core Principle: How Absolute Pressure Sensors Operate

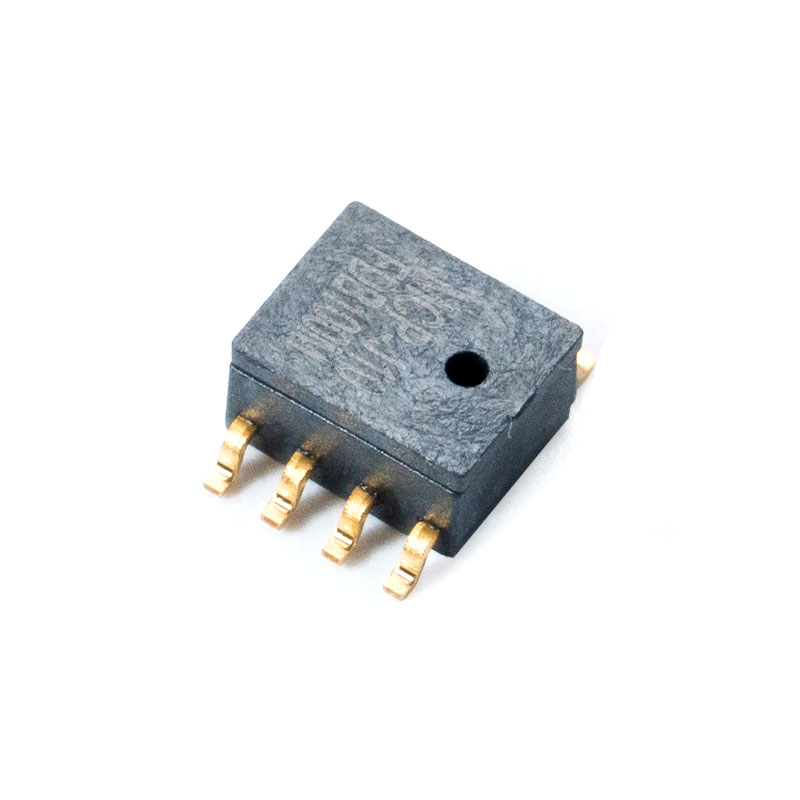

To fully grasp the value of an absolute pressure sensor, one must first understand its foundational principle and how it differs from other pressure measurement types. The term "absolute" refers to its zero-reference point: a sealed vacuum chamber within the sensor itself. This internal vacuum provides a constant baseline, ensuring measurements are independent of fluctuating local atmospheric pressure. This contrasts sharply with gauge pressure sensors, which use atmospheric pressure as their zero point, and differential pressure sensors, which measure the difference between two applied pressures. The ability to provide a true pressure reading is why these sensors are essential for applications like absolute pressure sensor for altitude measurement or barometric pressure sensing. Modern absolute pressure sensors predominantly utilize Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) technology. This involves etching a microscopic, flexible diaphragm directly onto a silicon chip. One side of this diaphragm is exposed to the vacuum reference, while the other is exposed to the pressure being measured. The resulting deflection is converted into an electrical signal, typically via embedded piezoresistive elements or capacitive plates, which is then conditioned and calibrated for output.

- Vacuum Reference Chamber: A hermetically sealed cavity within the sensor die creates the fundamental absolute zero reference, making the sensor's reading unaffected by weather or location changes.

- MEMS Diaphragm: The heart of the sensor, this micron-thin silicon membrane deflects minutely in response to applied pressure. The precision of its etching defines many performance characteristics.

- Transduction Mechanism: As the diaphragm bends, it causes a measurable change—either in resistance (piezoresistive) or capacitance (capacitive)—that is precisely correlated to the applied pressure.

- Signal Conditioning: Raw output from the sensing element is amplified, temperature-compensated, and linearized by an Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) to provide a stable, accurate, and usable signal.

Pressure Sensor Types: A Comparative Overview

| Sensor Type | Reference Point | Output Reads | Common Application Example |

| Absolute Pressure | Perfect Vacuum (0 psi a) | Pressure relative to vacuum | Altimeters, barometers, vacuum systems |

| Gauge Pressure | Local Atmospheric Pressure | Pressure above/below atmosphere | Tire pressure, blood pressure (cuff), pump pressure |

| Differential Pressure | Another Applied Pressure | Difference between two pressures | Filter monitoring, fluid flow rate, leak detection |

Key Specifications and Selecting a High-Accuracy Sensor

Choosing the right absolute pressure sensor requires a detailed look at its datasheet. Performance is quantified by several interrelated parameters that directly impact the reliability of your system. For applications demanding precision, such as diagnostic medical equipment or advanced engine control, selecting a true high accuracy absolute pressure sensor is non-negotiable. Accuracy itself is a composite specification, often encompassing initial offset error, full-scale span error, non-linearity, hysteresis, and, most critically, errors induced by temperature changes over the operational range. Other vital specs include measurement range, resolution (the smallest detectable change), long-term stability, and response time. Achieving high accuracy is a multifaceted engineering challenge. It starts with an optimized MEMS design for minimal mechanical stress and continues with advanced packaging that protects the die from external stresses. The sophistication of the onboard temperature compensation algorithm, often baked into the ASIC, is a key differentiator. This is where rigorous production and testing protocols prove their worth, ensuring each sensor is individually calibrated and verified against strict standards to deliver consistent, trustworthy performance.

- Total Error Band: The most comprehensive accuracy metric, it defines the maximum deviation of the sensor's output from the true value across the entire pressure and temperature range, giving a real-world performance picture.

- Temperature Compensation: High-performance sensors integrate temperature sensors and complex compensation curves in the ASIC to nullify the effects of thermal drift, which is the leading cause of inaccuracy.

- Long-Term Stability: This specifies how much the sensor's output may drift per year, a critical factor for systems where recalibration is difficult or for ensuring the longevity of a medical grade absolute pressure sensor.

- Production Calibration: A commitment to high accuracy involves end-of-line calibration at multiple temperatures and pressures, often using traceable standards, to program correction coefficients into each device.

In-Depth Application Analysis: From Sky to Vein

The unique trait of absolute pressure measurement unlocks a diverse array of critical applications across vertical markets. Each application imposes its own set of stringent requirements on the sensor, pushing the boundaries of technology in terms of environmental robustness, precision, size, and power consumption. Whether it's enabling a drone to maintain a stable hover, ensuring an engine runs at peak efficiency, or monitoring a patient's blood pressure continuously, the absolute pressure sensor is a silent enabler of modern functionality. By examining three key domains—altimetry, automotive, and medical—we can appreciate the specialized engineering involved in tailoring this fundamental technology to meet extreme and specific operational demands. This deep dive highlights why a one-size-fits-all approach fails and why application-specific design and manufacturing expertise are paramount.

Reaching New Heights: Absolute Pressure Sensors for Altitude Measurement

The principle is elegantly simple: atmospheric pressure decreases predictably with increasing altitude. An absolute pressure sensor for altitude measurement acts as a sophisticated barometer, translating subtle pressure changes into altitude data with remarkable precision. This functionality is central to aircraft altimeters, weather balloons, and increasingly, consumer electronics like smartphones, smartwatches, and hiking GPS units. For drones and UAVs, it provides essential data for altitude hold and terrain-following functions. The challenges here involve compensating for local weather-induced barometric changes (often via software algorithms) and ensuring the sensor has excellent low-pressure resolution and minimal noise. Low power consumption is also critical for battery-operated portable devices, making advanced MEMS sensors with integrated digital outputs the preferred choice.

- Low-Pressure Sensitivity: Sensors must be sensitive enough to detect the small pressure differences corresponding to meter-level altitude changes, especially at higher altitudes.

- Environmental Compensation: Algorithms often fuse pressure data with temperature readings from the sensor to improve altitude calculation accuracy under varying climatic conditions.

- Power Optimization: Consumer devices demand sensors with very low active and sleep currents, driving the need for highly integrated, power-efficient MEMS designs.

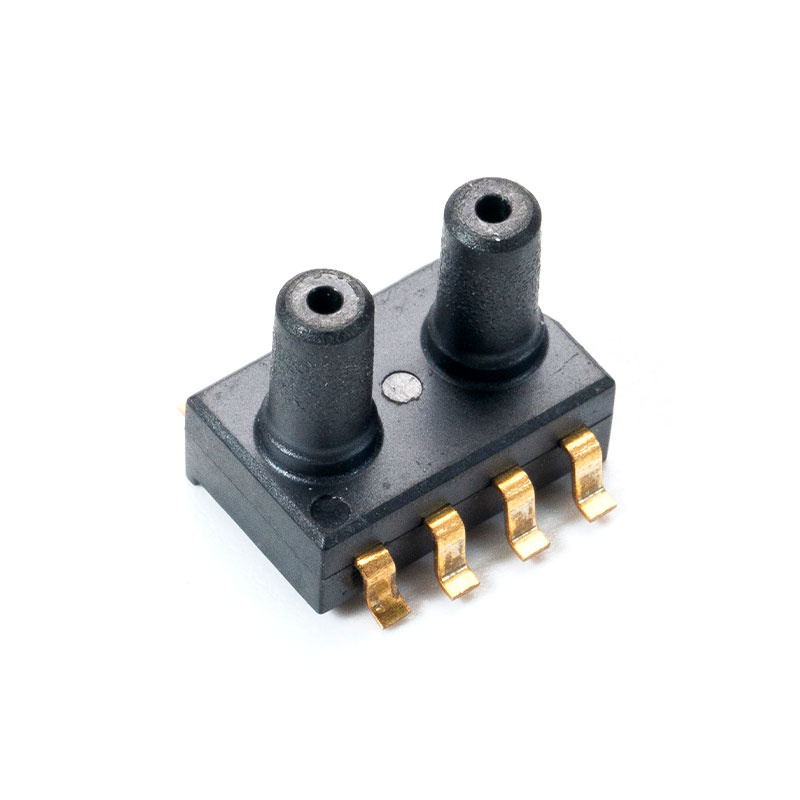

Powertrain and Beyond: Absolute Pressure Sensor Automotive Applications

The modern automobile relies heavily on absolute pressure sensor automotive applications for performance, efficiency, and emissions control. The most classic example is the Manifold Absolute Pressure (MAP) sensor, a critical input for the Engine Control Unit (ECU) to calculate air density and optimize the air-fuel mixture for combustion. They are also vital in fuel vapor leak detection systems (EVAP), brake booster systems, and even in advanced suspension and climate control systems. The automotive environment is exceptionally harsh, subjecting sensors to extreme temperatures (-40°C to 150°C), constant vibration, exposure to fluid contaminants, and severe electromagnetic interference. Therefore, automotive-grade sensors require rugged packaging, specialized protective gels, extensive testing for long-term reliability, and compliance with strict quality standards like AEC-Q100.

- High-Temperature Operation: Under-hood sensors must maintain accuracy and stability at sustained high temperatures, requiring specialized materials and design.

- Media Compatibility: The sensor's diaphragm must withstand exposure to aggressive media like fuel vapors, brake fluid, or oil without degradation.

- EMC/ESD Robustness: Electrical design and shielding must ensure reliable operation amidst the electrically noisy environment of a vehicle.

Life-Critical Monitoring: Medical Grade Absolute Pressure Sensors

In medical technology, the stakes for sensor performance are at their highest. A medical grade absolute pressure sensor is a key component in devices for direct and indirect blood pressure monitoring, ventilators, infusion pumps, and dialysis machines. These applications demand not just high accuracy and stability, but also unwavering reliability and strict adherence to safety standards. Medical-grade sensors often feature biocompatible packaging materials for use in invasive applications. They undergo rigorous qualification processes and must be manufactured in facilities compliant with ISO 13485 standards. Long-term drift must be exceptionally low, as recalibration in a clinical setting is often impractical. The transition to digital output absolute pressure sensor variants is strong here, as it facilitates integration with digital patient monitoring systems and reduces noise susceptibility in clinical environments.

- Biocompatibility: Sensors used in invasive applications (e.g., catheter-tip pressure sensors) must use materials that are non-toxic and non-reactive with bodily tissues and fluids.

- Regulatory Compliance: Manufacturing processes and product documentation must fully support regulatory submissions for approvals from bodies like the FDA (USA) or CE (Europe).

- Ultra-Low Drift: Exceptional long-term stability is mandatory to ensure patient monitoring equipment provides consistent, reliable readings over its service life, minimizing clinical risk.

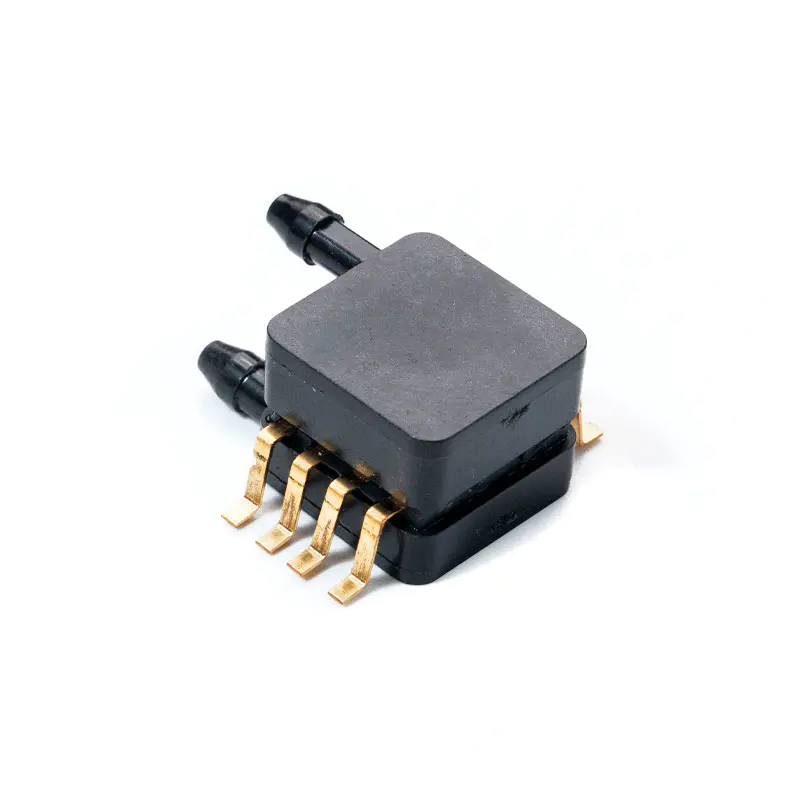

Interface and Integration: The Digital Sensor Advantage

The evolution of sensor technology extends beyond the sensing element to how it communicates with the broader system. While analog voltage or current outputs are still used, the industry is decisively moving towards digital output absolute pressure sensor solutions. These integrated sensors provide a direct digital readout, typically over standard protocols like I2C or SPI. This integration offers substantial system-level benefits. Digital communication is inherently more immune to electrical noise, which is crucial in complex electronic assemblies like engine control units or portable medical monitors. It simplifies design by reducing the need for external analog-to-digital converters and signal conditioning circuitry. Furthermore, digital interfaces allow the sensor to transmit not just pressure data, but also temperature readings and device status, and they enable features like programmable interrupt thresholds. For manufacturers, providing such integrated, easy-to-use components is part of delivering a complete, cost-effective solution that accelerates time-to-market for their clients in fast-moving industries like consumer electronics and IoT.

- Noise Immunity: Digital signals (I2C, SPI) are less susceptible to corruption from electromagnetic interference (EMI) compared to small analog voltage signals, improving reliability in noisy environments.

- Simplified System Design: Engineers can connect the sensor directly to a microcontroller's digital pins, eliminating external op-amps, ADCs, and complex layout concerns for analog traces.

- Enhanced Functionality: Digital sensors can embed significant intelligence, offering features like built-in averaging, FIFO data buffers, and programmable alarm functions that offload processing from the main host MCU.

- Streamlined Production: Using digital sensors can reduce the component count on a PCB, simplify the Bill of Materials (BOM), and potentially lower overall assembly and test costs.

FAQ

Do absolute pressure sensors require calibration, and how often?

All absolute pressure sensors require initial factory calibration to correct for inherent manufacturing variations in the MEMS diaphragm and ASIC. This calibration data is typically stored in the sensor's non-volatile memory. Whether they require recalibration in the field depends on the application's accuracy requirements and the sensor's specified long-term stability. For consumer applications like smartphone altimeters, field recalibration is generally not performed by the user. For critical industrial, automotive, or medical applications, periodic recalibration may be part of the system's maintenance schedule. The interval is determined by the sensor's stability specification (e.g., ±0.1% of full scale per year) and the system's tolerance for drift. A high accuracy absolute pressure sensor designed for critical measurements will have a very low drift specification, extending the potential time between recalibrations.

What factors are most important when choosing a sensor for altitude measurement?

Beyond basic accuracy, several key factors are crucial for an absolute pressure sensor for altitude measurement. First is low-pressure resolution and noise. The sensor must detect minute pressure changes corresponding to small altitude differences (e.g., 1 meter). High noise can swamp these small signals. Second is excellent temperature compensation, as temperature changes significantly affect pressure readings and can be misinterpreted as altitude changes. Third is low power consumption for battery-powered devices. Finally, for consumer electronics, a digital output absolute pressure sensor with a standard I2C or SPI interface is highly desirable for easy integration and noise-immune data transmission.

How do medical-grade pressure sensors differ from industrial ones?

A medical grade absolute pressure sensor is subject to far more stringent requirements than a standard industrial sensor. The primary differences are: 1. Biocompatibility: Any part exposed to the human body (in invasive applications) must be made of certified biocompatible materials. 2. Regulatory Compliance: They must be designed and manufactured under a Quality Management System compliant with ISO 13485, and support regulatory filings for FDA, CE MDD, or other regional approvals. 3. Reliability and Safety: Failure modes are rigorously analyzed (FMEA), and designs prioritize patient safety above all. 4. Performance: While accuracy is important, long-term stability and ultra-low drift are often even more critical to avoid frequent recalibration of medical devices. Industrial sensors prioritize factors like wide temperature range, media resistance, and cost over these medical-specific requirements.

Should I choose a digital or analog output pressure sensor?

The choice between digital and analog output depends on your system architecture and priorities. An analog output (e.g., 0.5V to 4.5V ratiometric) is simple and may be suitable for short cable runs in low-noise environments directly to an ADC. However, a digital output absolute pressure sensor (I2C, SPI) is generally recommended for modern designs. It offers superior noise immunity, easier direct connection to microcontrollers, simpler PCB layout (no analog traces to protect), and often includes integrated temperature data and advanced features. Digital is almost always the preferred choice for new designs in consumer electronics, portable devices, and complex systems where multiple sensors are used on a shared bus.

What does "long-term stability" mean in a sensor datasheet?

Long-term stability, sometimes called long-term drift, is a specification that quantifies the change in a sensor's output signal over time when operating under constant pressure and temperature conditions. It is typically expressed as a maximum percentage of full-scale span per year (e.g., ±0.1% FS/year). This drift is caused by aging effects within the MEMS structure and the electronic components. This specification is critical for applications where the sensor cannot be easily recalibrated after installation, such as in implanted medical devices, sealed industrial equipment, or absolute pressure sensor automotive applications like MAP sensors that are expected to perform accurately over the lifetime of the vehicle. A lower stability number indicates a more reliable and maintenance-free sensor.

English

English Français

Français 中文简体

中文简体